- Home

- Cynthia Lord

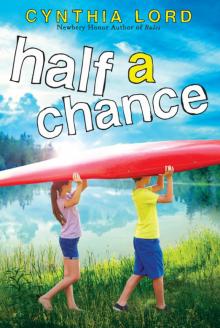

Half a Chance

Half a Chance Read online

To Robin

Contents

Title Page

Dedication

1 Out of Place

2 A New Day

3 Skip

4 Heading Home

5 At the Shore

6 Texture

7 Journey

8 Sticky

9 Wonder

10 Now and Then

11 Secret

12 Holding On

13 Collection

14 Design

15 Three Feet

16 Lost

17 Left Behind

18 Your Name

19 Unexpected

20 On Its Own

21 Beyond Reach

22 At the Crossroads

23 A Closer Look

24 Hope

About the Author

Copyright

“Lucy, we’re going to love this place!” Dad called to me from the porch of the faded, red-shingled cottage with white trim. “We can hang a swing right here and watch the sunset over the lake. And these country roads will be great for biking.”

While my little dog, Ansel, explored some ferns, I took a deep smell of the pine trees lining the dirt driveway.

“I’ll buy you a new bike when I get back, Lucy. Would you like that?” Dad asked.

“Maybe we can get two bikes,” I yelled to him. “So we can ride together.”

“Great idea!”

Dad always promises me things before he leaves and then forgets by the time he’s home again. But I couldn’t help having that little bit of “I hope so” that this place would be different. That’s the thing with new beginnings — sometimes, they’re more than just starting over again.

Sometimes they change things.

“There are more boxes in the van,” Mom said, carrying a laundry basket full of kitchen stuff past me and across the flagstones leading up to the front porch steps.

“I’ll get them in a minute,” I promised. “Ansel needs to stretch.” But really, I wanted to take my first New Hampshire photo before I went inside and everything got busy. Whenever we move, I take a picture as soon as we arrive. It always makes me feel a little braver, knowing that on some future day I can look back at that photo, taken when it was new and scary, and think, I made it. Like creating a memory in reverse.

On the drive from Massachusetts to New Hampshire, I’d been thinking about what my first photo would be. When Dad said he’d found us “a lovely red cottage on a lake,” it sounded fancy.

Dad always says that red is a great color in a photograph, so I thought for sure I’d take a picture of our new house. But this washed-out red seemed to disappear into the woods behind it. The gambrel roof and two long windows above the porch made it look like an old barn with white-rimmed, tired eyes watching the lake.

This house didn’t look like it was supposed to be quirky, though. It looked like whoever built it didn’t really know how.

So I turned to see what the house was looking at: the bright blue lake, puckered by darker waves, and the four mountains — three graceful curves and one sharp peak — rising above the pine trees across the water.

When we lived in Vermont three years ago, there were mountains, too, but this would be my first time living on a lake. “Let’s go down to the beach,” I said, but Ansel pulled backward on his leash. “It’s okay. You don’t have to go swimming. We’ll just look at the water.”

Ansel’s only fifteen pounds, but those fifteen can feel like a hundred when I’m tugging him to come and he’s pulling back: No way.

I had to carry him. Between the lawn and the lake were thousands of smooth, soft-colored rocks: white, gray, rust, yellow, and tan. They crunched under my feet, sounding like marbles rubbing together or Scrabble pieces as you mix them up. Flip-flops are the wrong shoes for this, I thought as my foot slid to the side.

Ansel’s nose twitched at the unfamiliar lake smell: weedy and a tiny bit fishy. Out in the middle, the water was sparkling-pretty, like someone had spilled a whole bottle of glitter out there. But up close, an icky border of bright yellow pollen floated along the lake’s edge. Beyond the pollen, a school of tiny minnows swam along, shifting directions quickly. This way! No, that way! Who’s in charge here?

When I set Ansel on the sand, he immediately leaned down to sniff a little brown moth that was stuck in the pollen, fluttering. The moth might already be too wet, too exhausted to live. But I found a leaf to scoop him out of the water and placed him gently on a rock so he could dry his wings.

Even half a chance beats none.

Holding my camera to my eye, I saw I had ruined my shot. Now the colors were too close: drab brown moth on drab brown rock. And there was no story. It was just a moth stuck to a rock.

Dad would’ve thought of the photo first. He would’ve shot the moth struggling in the pollen and found a way to make people care — even though it was just a plain, ordinary, dying bug. Dad’s an amazing photographer, and he says it’s just as important to show the hard things in the world as it is to show the beautiful ones. Even in the midst of horrible things, there are little bits of wonder, and all of it’s true.

Ansel barked. Switching off my camera, I glanced where his nose pointed. On the beach next door was a row of kayaks, and an older lady was standing on the dock. Sitting next to her were a boy and a girl, both about my age, with their feet in the water and towels draped around their shoulders. Smaller kids were swimming nearby, just their heads showing above the waves. “Grandma Lilah, watch me!” a small voice yelled. “I’m a water bug!”

Ansel barked again. “Hush,” I told him. “Don’t bark at our neighbors. They live here.”

The gray-shingled cottage next door looked how I had imagined a cottage on the lake would look: a fairy-tale house with bright-white painted lattice crisscrossing the tops of the bow windows and dormers jutting out from the roof. Baskets of red petunias hung on the long front porch.

Beside it, our cottage looked like a run-down summer camp on move-in day, with random boxes and suitcases and stuff in the yard.

Watching the neighbors having fun together at their pretty house made me feel lonely, not just alone. At twelve years old, I’d already moved three times in my life. I should’ve been able to march over there and say: “Hi, I’m Lucy. We just moved in,” and not be scared. Practice only made it familiar, though. Never easy.

Ansel barked again, and the boy on the dock looked over at us.

Uh-oh! I lifted my hand and swished it by my ear, so it could go either way: waving if he was friendly or brushing away a mosquito if he wasn’t.

The boy waved back, got to his feet, and started walking down his dock toward the beach.

Is he coming over here? I took a deep breath. Dad had driven us past my new school, and it was so small that any new girl would stick out immediately in September. It would really help if I made some friends over the summer.

I gave the boy my warmest smile. “I’m Lucy, and this is Ansel. We just moved in.”

“I’m Nate.” As he reached out his hand to Ansel, I gripped the leash. Ansel doesn’t love everybody.

“We’re sooo glad to meet you!” I said, in my sweetest, most singsongy voice, so Ansel would hear the “happy” in my voice and feel okay about the hand coming toward him. He took a glancing sniff of Nate’s fingers. His ears, which usually stuck up, stayed back, but the tip of his tail wagged.

Nate smiled, the freckles rising across his nose. There was a slight gap between his front teeth, which made his face interesting and a little funny and quirky — a good quirky. I couldn’t believe how comfortable Nate seemed only wearing shorts and a towel. I’d be cringing if I had to meet someone in my bathing suit.

“We noticed the FOR SALE sign was gone,” Nate said. “We were wonderin

g who would be moving in.”

“It’s us,” I said, and immediately wished I’d said something smarter. Of course it was us! “Though my dad leaves tomorrow on a trip to Arizona for his work, so it’ll be mostly me and my mom this summer.”

Ansel barked again, and I noticed the girl from the dock was coming up the beach, too. She wore glasses, and her long hair hung in wet pigtails.

“Lucy, this is Megan,” Nate said. “Her cottage is the yellow one down at the point.”

“Hi.” I gave her a bright smile.

Megan tipped her head a little sideways, looking at me over her glasses. “How long are you here for?” she asked.

“We’re going to live here,” I said simply.

“Cool,” Nate said, grinning. “My grandma owns our cottage. We live in New Jersey, and my family usually only comes for two weeks, but this year we’ll probably be here all summer!”

“I always come for the whole summer,” Megan said. “I know just about everyone on the lake — at least on our side. Our real house is in Connecticut.”

Neither of them went to school here. I froze my mouth in a smile so my disappointment wouldn’t show.

“Come on, Nate,” Megan said. “We’re supposed to be helping Grandma Lilah watch the little kids while they’re swimming.”

“Do you want to come over, Lucy?” Nate asked.

“We just got here,” I said. “I need to help unpack.”

“Okay. See you later,” Megan said.

Watching them walk away, I wondered if maybe I should’ve gone. Even if Nate and Megan didn’t go to school here, a summer friend would make things better now. And most times, kids decide if they’re going to like you really fast. Saying no might’ve blown my chances.

One thing I’d learned about moving was that once you were there, it was better to just look ahead. Because even if you went back to visit the places and people you left behind, it was never the same — except in photos. Those always keep everything exactly the way it was: a sharp-steepled white church against thunderclouds near our old house in Vermont, rainbow-colored graffiti on the overpass near our apartment in Boston, yellow window light slanting out across the wet cobblestones near our rented rooms on Nantucket.

I pointed my camera straight down and took a photo of my feet in my flip-flops on the shore with my toes almost touching the rim of yellow pollen.

New Hampshire: Day One.

Before dawn, I woke to an eerie wavering cry, wild and lonely.

For a moment, I panicked, not even remembering where I was. Then, with a big “oh, yeah,” it all came back: New Hampshire, our tired-looking house, the lake, Nate who seemed friendly and Megan who didn’t. Today, Mom and I would be driving Dad to the airport for his trip.

In the damp almost-morning, even the dark felt like someone else’s. On top of the covers, Ansel let out a low growl. “Shh,” I said, reaching down to pat his back. “It’s okay. Whatever is making that weird sound is staying outdoors.”

Mom hadn’t wanted a dog, but a few months ago, Dad had returned from a photography trip to Montana holding a dog carrier. Peeking out of the front was a scruffy, mixed-breed, black-and-white dog. “Meet Ansel,” Dad had said, naming the dog for Ansel Adams, a famous photographer who had shot beautiful black-and-white photos. Mom said our landlord would have a fit, but Dad said Ansel was a stray and all alone, and Dad couldn’t leave him that way. “Somehow, it’ll work out,” he said.

Here’s how it worked out: The landlord told us to leave.

Dad probably wouldn’t admit it, but I think he was relieved. He craves moving the way other people crave staying put. After we move he’s fine for a while, but then he starts looking at maps and websites. “I’ve taken all the photos I can of this place,” he’ll say.

But really, I think Dad loves how good it feels to leave — to let go of the routine in an old place and start over somewhere else.

The mournful sound came from outside again. I shivered, climbing out of bed to shut the window. The lake was an open, lapping darkness except for shifting speckles of moonlight on the surface.

Below, on our beach, I could make out Dad with his tripod.

I ran my hand over the wall beside the door frame, feeling for the light switch so I could get dressed and find my camera on the old wooden bureau some previous owner hadn’t wanted to take with them. Everything creaked: the wide floorboards, my room’s antique brass doorknob, and the heavy, white-painted door. “I’ll be back,” I whispered to Ansel.

By the time I got to the beach, the sky already glowed dusty blue. “Hey, Lucy. I hope I didn’t wake you,” Dad said. “I thought I’d shoot our first New Hampshire sunrise.”

“Me, too.” The early morning was so quiet that I could hear the waves hitting the beach, the leaves moving, and the birds chittering. From somewhere far away, a train whistle blew.

Across the water came that haunting call again. “What’s that sound?” I asked. “It sounds like a wolf howling!”

“That’s the loons,” Dad said. “They’re black-and-white waterbirds, a little bigger than a duck and a bit smaller than a goose.”

“Birds are making that sound?” I asked. “Are they going to do that every morning?”

He smiled. “Probably. But they’ll only wake you up this time of year. They come to the lakes in the spring to fish and raise their chicks. But in October or November, they’ll leave to spend the winter on the ocean. Really, we’re lucky to have them — they are a threatened species in New Hampshire.”

“I bet it’s their neighbors who are threatening them!” I joked. “Because they’re annoyed to be woken up.” I felt a tiny jab on my neck and slapped at the mosquito. Where there was one, there were sure to be a hundred more coming. “Do you want some bug spray?” I asked.

Dad didn’t look up from his camera, so I dug around in his backpack until I found it. I don’t like the sticky, tight feeling of bug spray on my skin, but bug bites are worse.

As pink blushed the horizon, I looked for a good subject for my shot. No need to think about the background — that’d be the lake and the morning sky. But I needed something for the foreground. The left-behind lawn chair on Nate’s dock might make a pretty black silhouette. But I’d have to walk on their beach to get a good shot. “Do people own the beach? Or just their lawn?”

“I don’t know,” Dad said. “But it doesn’t matter. We’re the only ones awake this early.”

The surrounding cottage windows were all dark. Maybe Dad was right and no one would know. As the sky was deepening into mauve and blue, I hurried to find a spot on the sand near Nate’s family’s dock.

“Here it comes!” Dad called.

A streak of sun surged over the mountains on the far side of the lake. I shot and shot, trying different angles and positions of the chair against the sky.

Dad took a few pictures and then quickly moved his tripod to a different place. Sunrise and sunset give some of the best light all day: warm and golden. But it comes and goes like that.

We were shooting the same sky, but I already knew his photos would be better. For one thing, he had a fancier camera. Mine was just a point-and-shoot camera with some extra settings and a bigger, better lens than most. But it wasn’t just his expensive camera or the fact that Dad had more experience that made the difference. You could call it having “a good eye” or talent, but it’s what adds the spark. And whatever you call it, Dad has it.

The sky was light blue now, but the clouds were sugary pink.

“Isn’t it something?” Dad said.

The black jagged line of pine and spruce treetops across the lake made a nice contrast against the pink and orange clouds. But when I turned on the camera’s LCD screen and looked at my photos, none of them captured how beautiful it was in real life. None were good enough to impress Dad.

When the sun was a hot ball above the trees, we turned to see what the sunlight was slanting across to touch.

“Those three kayaks on the beach wi

ll make a good shot.” Dad nodded at a row of overturned kayaks on Nate’s beach. “From the dock, I can get a good, clean background.”

It might be iffy who owned the sand, but there was no question who owned the dock — not us. What if someone at Nate’s house looked out the window and saw Dad and thought we were pushy people who didn’t care about what was ours and what wasn’t? The wooden planks squeaked with his footsteps. But no one came running out of the house to tell us to go away, so I knelt beside the bushes at the edge of the lawn.

Sometimes you miss little things when you stand over them and look down. Sure enough, strung among the leaves of a blueberry bush was a perfect, teeny spiderweb, shining with beads of dew. At the bottom of the web was a fat black spider. I tried so many angles of that web that my knees hurt from kneeling so long. I clicked on the camera’s screen to see my shots. A close-up picture is like entering another world where little things are gigantic. I scrolled through to find my best spiderweb photo.

As I walked over to Dad, I was excited to show him something he hadn’t seen. “Not bad!” he said as we looked at it together. “See how the light is hitting every strand? It doesn’t even have a good background, but the light on the waterdrops shows it off beautifully.”

“I found it, though,” I said under my breath, annoyed that he had given all the credit to the light.

“Hello,” someone called.

My heart jumped to see the old lady from next door in her yard. “Are you going out to see the loons?” she asked.

“Your kayaks look so beautiful in the morning light,” Dad said. “I was taking a photo of them. Would you like to see?” Mom always says Dad has a way with people. He just smiles and starts talking and people love him. I wish he’d passed that way on to me. It’d be a whole lot more useful than just giving me his stick-straight brown hair and his blue eyes.

He walked up on her lawn to show the woman the photo on his camera’s screen. “I’m Dan Emery, and this is my daughter, Lucy. We’ve just moved in next door.”

“You can call me Grandma Lilah. Everyone does.” She smiled as the loon wailed again. “The loons have a nest on a little island across the lake. Some years they lay just one egg and other years they lay two.”

Merlin

Merlin Rules

Rules Half a Chance

Half a Chance Jelly Bean

Jelly Bean A Handful of Stars

A Handful of Stars Paloma

Paloma Touch Blue

Touch Blue Because of the Rabbit

Because of the Rabbit